19. THE BEAUFORT LEGITIMATION

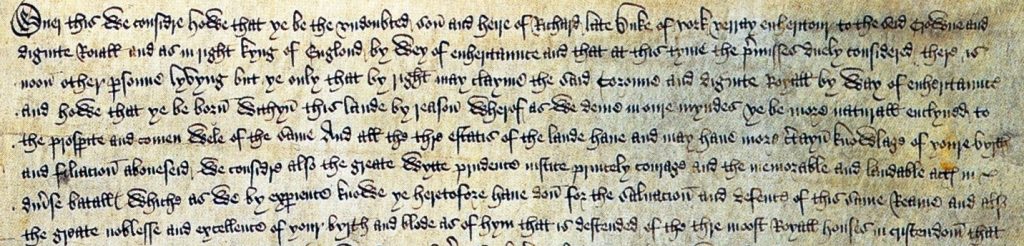

Henry Tudor, later Henry VII, claimed entitlement to the crown of England ‘by due and lineal inheritance’. His only English royal blood derived from his great-grandfather, John Beaufort, an illegitimate half-brother of Henry IV. The Beauforts’ father, John of Gaunt, had them legitimated by Richard II in 1397 by Act of Parliament. This article investigates the Act of Legitimation and proposes that (1) the Act gave them no rights of inheritance, and (2) Richard II was wrongly informed that the Pope had granted them legitimacy. Read it now by clicking on this link: https://tinyurl.com/ur2p8rc4

Henry Tudor, later Henry VII, claimed entitlement to the crown of England ‘by due and lineal inheritance’. His only English royal blood derived from his great-grandfather, John Beaufort, an illegitimate half-brother of Henry IV. The Beauforts’ father, John of Gaunt, had them legitimated by Richard II in 1397 by Act of Parliament. This article investigates the Act of Legitimation and proposes that (1) the Act gave them no rights of inheritance, and (2) Richard II was wrongly informed that the Pope had granted them legitimacy. Read it now by clicking on this link: https://tinyurl.com/ur2p8rc4

18. INVESTIGATING HENRY VII’S REPEAL OF TITULUS REGIUS

What did Henry Tudor achieve by repealing Titulus Regius, Richard III’s 1484 Act of Succession? He wanted everyone to think he had revoked the illegitimacy of his proposed wife, the princess Elizabeth of York, and the world has obligingly believed him. But a repeal is not a conjuring trick, it’s an item of legislation, which is capable of doing only what the law says it does. Today I am offering a new article, taking you through what really happened. Just click here: https://tinyurl.com/d6tmxya4

17. Sir George Buc's History of King Richard the Third - new edition by Dr Arthur Kincaid

At last, after 18 months’ work on my part – and 50 years by Arthur Kincaid!) – Arthur’s new edition of Sir George Buc’s defence of Richard III has been published.

Arthur published his first edition of Sir George’s authentic text in 1979, with the expectation that historians would recognize the difference between this scholarly work (previously unpublished) and a certain bastardized version published in 1646 by ‘George Buck Esquire’. The name of the author should have provided a clue.

The scandalous story of how Mr Buck stole Sir George’s manuscript sends shudders down the spine of every writer, as does the result: it was so bad that it trashed Sir George’s reputation for three centuries because it was thought to be his book.

Arthur hoped his edition of 1979 would vindicate the original author’s meticulous work and his cogent arguments for reassessing King Richard’s reputation. But historians both professional and amateur stuck to the old 1646 book they were used to, and Google Books even published it (horror of horrors) under the name of poor Sir George. [And nothing so far can persuade them to correct the attribution.]

I won’t go into the sad catalogue of ways in which Sir George was doubted, questioned and even accused of practising deceit. How the awful 1646 travesty was actually re-published while Arthur’s authentic edition of the real thing was virtually ignored. And how he signed a contract with a 21st-century publisher who sat on Arthur’s files containing this revised edition for five years and then dumped the project.

I had a personal responsibility in this because I’d encouraged Arthur when he told me, while we were attending the reburial of Richard III in 2015, that he had long desired to produce a revised edition reflecting all we have learnt in our researches over the last four decates. I urged him to do it, knowing it was a massive undertaking, and offering my assistance with updating research, tracking down sources, editing and proof-reading. So I have lived with this endeavour for the past eight years!

It was when Arthur, now diagnosed with lung cancer, heard from his publisher in 2021 saying he didn’t foresee publishing the book, that Arthur appealed to me to rescue the project. By this time his health and memory were becoming fragile, but I acquired all his files and set about looking for a new publisher – none too easy with an academic work of 300,000 words which had scarcely lit up the world of history at its first outing! We managed to work our way through the queries I found, and emerged with a text sufficiently ready to submit to my first choice of publisher, the Society of Antiquaries of London.

The Antiquaries’ non-profit status meant that money had to be found to fund the cost, but here I was blessed with two opportune ingredients. First, I felt it was a perfect book for the Richard III Society to underwrite if I could get their agreement (fortunately, Arthur is revered by the present Board of Directors, and they were willing to listen to me as a Fellow of the Society). The second ingredient was Barnwell Print, the wonderful firm of printers with which I have published books for many years, who agreed they could master the complexities of the text layout – and thereby I was able to produce a costing.

When both the Antiquaries and the Richard III Society gave it the thumbs-up, Arthur was thrilled at such a perfect collaboration. My next task was to procure the illustrations (and construct a family tree) and undertake a fourth reading of the whole book preparatory to handing over the files to Barnwell’s. The cross-references alone (150 of them) took me two weeks because Arthur, alas, was unable to help. Soon afterwards he was admitted to hospital, and we lost him on 24 Jult 2022. But he died knowing with certainty that his great work would soon be in print.

By the time the editing and corrections were done, I had read it through five times and knew it quite well. The cover was designed by the Antiquaries, featuring the Paston Portrait of Richard, of which Arthur thoroughly approved.

The book was printed and bound in January, but the planned launch couldn’t take place until members of both Societies had been informed and given the option to attend. So my work now centred on promotional material for use by the distributors here and in the US, and of course notices to be placed on the Richard III Society’s website and social media outlets.

I said goodbye to Sir George Buc at a launch held on 4 April 2023 at Burlington House, the HQ of the Antiquaries, when my last contribution was the keynote speech in tribute to Sir George, defender of King Richard, and Arthur Kincaid, defender of them both.

16. The Mysterious Affair at Stony Stratford

A tip of the hat in my title to Agatha Christie’s centenary, 2021 … this is my full-length article examining the events of 29-30 April, 1483, at Northampton and Stony Stratford. Read it or download it at your leisure, it’s over 20 pages long.

15. Why bother with this new Mancini?

There are two extremes when it comes to Mancini’s de occupatione regni Anglie. One extreme thinks the old translation of 1936 was just fine and the notes gave a reasonable smattering of background. The other extreme dismisses Mancini out of hand, saying his account is worthless because it’s biased.

Both these opinions miss the wealth of information available from reading it afresh, especially in more accurate and even-handed English. And particularly when you have the guiding hand of a NEW editor drawing attention to the important things so you don’t miss them!

You may be surprised to know that Mancini was actually less biased than his original translator John Armstrong. Mancini formed his opinions based on what was going the rounds in 1483: we know this, therefore we can put it into context and learn interesting stuff from it. By contrast, Mr Armstrong distorted Mancini’s words by overlaying them with his own post-Victorian, post-Shakespeare and post-Thomas More prejudices. He even cited ‘More and Shakespeare’ as sources in an article in The Times which I’ve included in the book to show just how prejudiced he was.

OK, we all know that Armstrong’s edition was so dry as to be practically indigestible – and this is what worries me. I’m sure many people won’t buy mine because they’ll think it’s the same. Well, you couldn’t be more wrong. Some very respected historians have drawn some very lazy conclusions and accepted too many well-worn assumptions. I have not been shy to skewer them.

You surely wouldn’t expect me to publish a new book that didn’t have a stack of new ideas and opinions in it, would you? Were you even aware how little the Mancini report had been seriously analysed before I came to it? Yes, we’ve all quibbled here and there with Mancini’s inferences and Armstrong’s translations. But if you want to appraise it as a whole you need to read the entire thing, preferably in the company of a guide like me who knows it word for word.

Above all, you’ll find I’ve put forward some quite radical ideas about how Mancini came to influence the Ricardian legend. Ever since the notion was proposed by Armstrong, we’ve grown used to the assumption that Mancini’s little book immediately disappeared into some vast black hole never to emerge until 1934. I.e. because it was (supposedly) never generally known, it was an entirely new yardstick against which historians could check whether Vergil and More and the rest were writing truthfully. If what they wrote was found also in Mancini, then their ‘facts’ must be right, mustn’t they?

I don’t know why this blinkered Anglocentric belief-system ignored all the chroniclers on the Continent of Europe at that time, who were eagerly garnering all manner of records to inform the massive books of history they were compiling for their patrons. My argument – which I know will ruffle many feathers – is simply that Mancini and his literary circle informed subsequent chroniclers including Vergil and More, so it’s a ridiculous idea to think that More is right because Mancini says the same thing. To prove my point there’s a well-known error in chronology that occurs in Mancini and the identical error is widely found in Tudor writers. Generations of historians have been scratching their heads about this ‘coincidence’, whereas my answer is that Mancini actually started it!

I can promise there’s a lot that’s well worth reading in my new edition of Mancini (have I ever let you down yet?). It’s not simply a more accurate translation of an old Latin text.

What worries me, as I said, is that fewer people are supporting writers like me. I’m putting in the effort to do all this crunchy research and self-publish books at my own expense which commercial publishers won’t touch. If they keep losing money, as they have done recently, the well will run dry. A lot of people who write fiction and popular history (and produce Ricardian CDs) have benefited from ideas derived from my books. The price of admission to all my work on the new Mancini – all the skill and analysis and brand-new insights – is just £10. It’s only a little book, but it will last you a lifetime.

14. New Mancini published 22 February 2021

My book Domenico Mancini: de occupatione regni Anglie is now available from the distributors: Domenico Mancini – Troubador Book Publishing.

It was over five years ago that I argued for a new edition of Mancini to replace the outdated original published in 1936. I had hoped the Richard III Society would put its considerable resources into this commission, especially as the text is less than 7,000 words – not a huge challenge for a competent Latinist. Sadly it was not to be. So I did it myself.

The reason this document is so important is that it is the only report written in 1483 by an eye-witness to the events from Edward IV’s death to Richard III’s accession. Every historian cites it when writing about Richard III. And the reason why it needs a new edition is that the 1936 translation suffers from so many shortcomings.

First, the translator held firmly to the view of Richard as murderer and usurper, and the language used in his translation reflects his prejudices. Even the title he invented was a deliberate mis-rendering of what Mancini wrote. The result failed to convey the full and proper meaning of much of Mancini’s own language, and failed to indicate the subtle progress of his thinking as he made his case to his readers. This is a major fault in the work of any translator, and especially when students who have no Latin are forced to rely on the translation’s integrity.

Second, the original edition failed to flag up the visible and consistent errors made by Mancini in his understanding of England’s legal and governmental system. Which is quite important when you consider that this was what Mancini was writing a report about! Worse than this, the translator himself made no attempt to disentangle Mancini’s confusion, presumably because as long as it condemned Richard III, it didn’t matter to him how inaccurate were the terms of the condemnation. So the misinformation of the reporter is compounded by the less-than-perceptive translation.

A third disservice to those wishing to understand the context of Mancini’s report is the inadequacy of the historical information, both in the original and in subsequent editions. Of course one can scarcely take the editor to task for not knowing then what Richard III specialists know now. But we are, I think, permitted to wonder why the Richard III Society felt this was in no particular need of updating. Especially as the main sources which are cited as authorities for comparison, throughout the historical notes, are those Tudor chroniclers that are nowadays recognized as so derivative and unreliable.

There is much more to be said about Domenico Mancini, his influences and sources, and the after-effects of what he wrote. All this is addressed in a full analysis in my new edition, together with 40 pages of historical notes to the text. If nothing else, I hope my new edition will be worth reading for the application of 21st-century scholarship to this seminal 15th-century text.

13. "A New Mancini?"

In an article in the Richard III Society’s magazine (December 2015) I drew attention to some of the errors about England that can be found in seminal texts written by foreigners. Henry VII favoured the encouragement of recently-arrived foreigners to write up his version of history, knowing that they would accept his authorized version in the absence of any personal knowledge to the contrary. This conveniently laid the basis for the disparagement of Richard III that became orthodox in the Tudor era.

There is another foreign writer, not (so far as we know) associated with Henry, whose narrative about an important period in Richard III’s career has also survived.

This is Domenico Mancini, an Italian who came to England in 1482, at the behest of

Not Mancini but a scribe to the Dukes of Burgundy

Angelo Cato (a leading light of the French court and a diligent intelligence-gatherer) to whom Mancini addressed a report which was discovered in the 1930s. Its finder, Mr C.A.J. Armstrong, translated and published it with an introduction and footnotes.

Its context was as follows. In the final months of 1482 King Louis XI of France had broken a recently-renewed treaty with England, terminated the annual pension he was paying to King Edward IV, and insolently jilted the king’s daughter who was betrothed to marry the Dauphin. Mancini was sent to England around this time as (it seems evident to me) one of the French court’s providers of foreign intelligence tasked with reporting back on the reaction of the English and their appetite for reprisals. It was, of course, an act of extraordinary French belligerence and Edward IV in his ensuing Parliament vowed himself determined upon revenge.

By sheer coincidence Mancini then found himself still present during the early months of 1483, a period whose importance eclipsed that of his previous mission. Ill-equipped in terms of any familiarity with England’s monarchy, its officers of state, its constitutional affairs, and its legal and historical precedents – and, apparently, unfamiliar with the English language – nevertheless Mancini was the man who happened to be on the spot and a report was demanded of him.

It isn’t my intention here to enter into an analysis of Mancini’s work. It is, however, relevant to remember that he already had a reputation as an accomplished writer and felt it necessary to compose not merely a journal of events, but an argument setting out his perception of how the king’s uncle (who became Richard III) fuelled by ruthless ambition, seized the throne from his hapless nephew.

The French governing classes already harboured a horror of the English habit of deposing their kings, and Mancini was writing for an audience eager to hear the worst of France’s ancient enemy across the Channel. The result is laced with gossip about royal scandals, and sorely lacking in reliable first-hand information that we can ascribe to Mancini himself.

In my latest book and in talks and articles about the offices of Protector and Constable I have explained at length how a fundamental misunderstanding of the role of England’s Lord Protector has taken hold, and how its earliest manifestations can be seen in the writings of foreigners like Domenico Mancini, Bernard André and Polydore Vergil.

John Armstrong’s edition of Mancini (somewhat updated in the 1960s) scarcely represents the range of expertise on Richard III that a modern scholar would call upon. Yet it’s been a source of surprise to me that those who write the history of Richard III’s period have allowed errors of fact in his text to pass without comment. If specialists appear to accept them without challenge, it is no wonder that they have become entrenched and generations of historians and commentators will continue to repeat them.

In an article in the Richard III Society’s Bulletin in 2015 I made a mild suggestion of ‘a more critical edition with a more accurate translation’. This was seconded by readers’ letters in subsequent issues.

Imagine my astonishment when this was rudely slapped down in a letter to the editor written by two people at the centre of the Society (one being its President), rubbishing the idea of ‘a new Mancini’. This letter preposterously assumed that we were calling for ‘a counterweight translation’ giving ‘the interpretation most favourable to Richard in every case’, which would expose the Society to ‘academic ridicule’. I have never proposed anything remotely of this sort, nor do I have any recollection of anyone else doing so. So it was profoundly depressing to see the suggestion of a serious new work of scholarship dismissed so scathingly.

Yet there would be ‘no problem,’ the letter condescended, ‘with such a Ricardian translation (clearly labelled as such) being made available to members through the Papers Library’. Really? Who would actually want to see such a travesty? Is this what the Society’s élite imagine the rank-and-file are avid for – some conjuring trick that transforms Mancini’s original hostile narrative into something ‘Ricardian’ (by which they clearly mean ‘partisan’)?

So in 2016 I quit writing about Richard III in disgust and wrote a biography of Captain DV Armstrong for Pen & Sword (which has met with huge critical acclaim). However, confined to my house last year in lockdown, I thought I’d make my own translation of Mancini. With introduction and historical notes fit for the 21st century. I rather enjoyed it, so it’s just gone to the printers. No, it’s not ‘a Ricardian translation’, and it won’t be going anywhere near the Richard III Society’s Papers Library LOL. Watch this space for further news …

12. The Death of Edward of Middleham, Prince of Wales

© Annette Carson 2020

One of the greatest personal travails endured by Richard III was the loss of his young son who died some months short of his eighth birthday. For a long time after hearing of this sudden tragedy, the Crowland Chronicle reported, his parents were almost out of their minds with grief.[1] And underlying this loss was the blow to Richard’s newly established dynasty.

A weird tradition has arisen around the date, which is that Edward, Prince of Wales died on 9 April 1484, twelve months to the day after the death of

his uncle and godfather, Edward IV, and this date even received confirmation in an article in the 2014 edition of The Ricardian.[2] The best-known report usually taken into account is that in the Crowland Chronicle, written in about 1485, which informs us that the King and Queen were in Nottingham at the time: ‘In the following April, on a day not far off King Edward’s anniversary, this only son, on whom … all hope of the royal succession rested, died in Middleham castle after a short illness’.[3] This widely quoted comment does NOT say he died on 9 April, but it is key to the negative view that this date was an ill omen, reinforced by the chronicler’s acid remark that it served as a lesson in the vainglory of man.

It is easy to forget that Edward IV had another anniversary associated with his death that the Crowland chronicler might also have had in mind, as a man of the cloth – which was that the late king’s fatal illness in 1483 had occurred around the holy festival of Easter.[4] I would contend that had the young prince died upon the actual anniversary of any such doom-laden date, we may safely assume this hostile chronicler would have made an even greater fuss of its moral significance. When recording the death of Richard’s heir as ‘not far off King Edward’s anniversary’, it is quite likely that Easter was embedded in this cleric’s mind (as recorded in his own chronicle) rather than the exact day of the month. Incidentally, although in normal circumstances we might expect any chronicler to reel off the dates of regnal years, which were reckoned from the monarch’s accession, the date of Richard’s accession was not helpful as an aide-mémoire in this respect because of the intervening few months of Edward V’s reign; this meant that, even when writing only about 18 months later, the Crowland author might still have failed to remember the exact date of Edward IV’s death.

Less well known is the comment by the Warwickshire priest John Rous, writing within five or six years of the occurrence, to the effect that Edward died ‘at Easter-time’ (tempore Paschali).[5] Easter Day in 1484 fell on 18 April. Little notice has been taken of this by traditional historians, but although Rous changed his coat to suit his political masters, he can be useful on matters of objective fact, especially those pertaining to the Beauchamp family of the boy’s mother, Queen Anne. They were his patrons and he spent years of his life documenting and eulogizing them. By the way, in connection with chroniclers forgetting dates, it is notable that by the time he came to describe the battle of Bosworth (Henry VII’s date of accession) Rous had forgotten the date and had to leave a blank in his manuscript.

In connection with Edward of Middleham’s death, even less attention seems to have been paid to the date at the very end of April – Tuesday the 27th – on which Richard left Nottingham for the North after hearing the dreadful news.[6] The date of the king’s departure is significant when weighing up the widely believed association of the date of his brother’s death with that of his son. Above all it is necessary to note that although we know nothing of the illness that killed little Edward, we do have one clue in that the Crowland Chronicle described it as brief and sudden (which would seem to rule out the idea, often suggested, that he died of tuberculosis).

So let us start chronologically by considering the well-known assertion that the Prince of Wales died on 9 April, which means he fell ill at the beginning of the month. If so, with Middleham easily accessible from Nottingham and with Easter on the horizon, his parents would surely have hastened to his side immediately: they had been in Nottingham only since about 4 April, so the royal entourage had not become so well entrenched there that a quick departure would have presented major difficulties. Haste would also have been necessary so as not to be delayed by the limitations of the impending holy season. These limitations were twofold: as king, Richard’s movements during mid-April would have been constrained by a prescribed royal schedule that began with duties during Holy Week (Maundy Thursday, etc.); and as a member of the Church he then ran into travel restrictions on Easter Day, 18 April, and the following Monday–Wednesday, detaining him until 21 April. Yet, far from departing before Easter to avoid such constraints, we find Richard remaining in Nottingham all the way through to 27 April. This is relevant even if we stretch that putative early April date to allow for the news to arrive at any time before Easter, for we still come up against Richard’s late departure date of 27 April when he would have been free to leave five days earlier. This seems conclusively to rule out news early in the month that his son was either deceased or in a serious condition.

Having set aside a date of death for Edward of Middleham before the approach of Easter, let us look at a possible date from Easter onwards. Observing travel restrictions, the earliest a mounted messenger could properly be sent from the ducal residence at Middleham would have been on Thursday 22 April: an urgent departure at dawn as soon as permitted would have brought the sad news to Nottingham late that night or early the following morning, Friday 23 April.[7] Even had the priests at Middleham waived the Easter travel strictures to enable the messenger to bring the news earlier to Nottingham, it is still more than likely Richard himself would have observed the restrictions by delaying his departure, especially if the news he received was not of illness but of death, meaning that no amount of haste could take him to his son’s bedside.

True, Richard might have chosen to leave very quickly to deal with the aftermath at Middleham and to oversee his late son’s funerary arrangements himself. Even, at least, to say his last farewells. But this is contradicted by his known movements: when he departed the following Tuesday, 27 April, he made his way from Nottingham to York where he had ceremonial commitments to fulfil. His failure to hasten to Middleham suggests that some time must have elapsed since Edward’s demise – so much time that there had been no option but for the Middleham household to make all the necessary arrangements already, indicating that it was too late for Richard’s presence to be relevant (as reigning monarchs he and Queen Anne would not, in any case, have attended any funeral ceremony). Once again we are looking at an Easter-time date which accords with Rous.

It has been observed, in Marie Barnfield’s article on this same subject (prompted by myself) in the Ricardian Bulletin of September 2017, that although Richard’s pattern of issuing dated documents dealing with government business whilst in Nottingham generally ran to between two and four per day, it changed abruptly on 24 April ‘with 16 documents being generated on 24 April and a further 10 on the 25th’. Although Ms Barnfield felt it was not possible to determine a reason for this, it might well tie in with the arrival of life-changing news the previous day, necessitating urgent attention to matters needing to be brought forward for settlement before an earlier than planned departure.

A relevant clue is that neither of the two clerical chroniclers (Crowland and Rous) actually stated a particular date of death, even though all indications point to its being around the holy Easter festival. Surely they would both have remembered very vividly if Edward had died on Easter Day itself, it being the clerical habit to indicate dates by a process of reckoning how near they fell to the closest landmark holy day or saint’s day – and Easter was the most important religious date of the year. That Richard’s brother and son both fell ill at Easter may well have been what prompted the Crowland chronicler to remember and remark upon the nature of the anniversary, but if so, he certainly had no recollection of its occurring on Easter Day itself.

Incidentally, all we know of Queen Anne at this time is that she was with Richard at Nottingham Castle to hear the news and that ‘for a long time’, as the Crowland Chronicle recorded, both parents could be observed ‘almost out of their minds … when faced with the sudden grief’.[8] How long was this lengthy grieving, and why did it occur at Nottingham rather than at Middleham? Again it suggests that their movements were restricted when it happened and their departure delayed by religious convention.[9]

In summary, therefore, although we cannot pin down Edward’s death exactly, we may make some assumptions.

(a) We can rule out a date of death much BEFORE Easter: if he died before this date, Richard could have got to Middleham before Easter commitments and travel restrictions began, or immediately after they ended – but he remained in Nottingham, and stayed there for a further five days after religious strictures ceased.

(b) A date much LATER than Easter (and nearer 27 April) seems to be ruled out because if so, Richard could have hastened to Middleham to bid farewell to his son’s mortal remains and see to funerary arrangements – but instead he went to York.

(c) A date of death AROUND Easter Day can be clearly reconciled with what little we know, and would explain why the arrival of news came too late for the parents’ presence to be relevant. It fits with the report of John Rous … and that of Crowland if the chronicler was recalling that Edward IV’s fatal illness occurred at Easter 1483.

This leaves us with the result that Rous was probably right in saying that little Edward did indeed die at Easter-time 1484 – although not ON an actual religious holy day – which suggests a day or two before Easter, taking us to April 16 or 17.

N.B. Further confusion surrounds Edward’s burial place, which for some years was inappropriately thought to have been at Sheriff Hutton. Documentation is lacking, but John Rous recorded in the Latin ‘Rous Roll’ (British Library) ante parentes infans obijt et apud Midleham honorifice sepulture traditur. This has been translated in different ways, so when I come across a disputed Latin text I habitually consult a friend who is a distinguished lexicographer of mediaeval Latin. His translation is as follows: ‘the child died before his parents and is committed honourably to burial at Middleham’.

It was not unusual to give a temporary resting place to a decedent of a noble house, pending arrangements for permanent burial at the family’s mausoleum or other suitably splendid place.

NOTES

1 The Crowland Chronicle Continuations, 1459-1486, ed. N. Pronay and J. Cox (London, 1986) pp.170–1 (hereafter C.C.).

2 A.F. Sutton et al, ‘The Children in the Care of Richard III’, The Ricardian, 2014, p.39. An earlier date of 31 March appeared at one time in the Complete Peerage (2nd edition, 1910–59, Vol. V, p.742).

3 C.C. pp.170–1.

4 C.C. pp.150–1: ‘the king … took to his bed around the feast of Easter’ (circiter festum Paschae). Easter 1483 fell on 30 March, which may have some relevance to the date mentioned in Complete Peerage [see note 2 above].

5 Joannis Rossi Antiquarii Warwicensis Historia Regum Angliae, ed. T. Hearne (2nd edition, Oxford, 1745), p.217. Translated in A. Hanham, Richard III and his Early Historians 1483–1535 (Oxford, 1975), p.123.

6 R. Edwards, The Itinerary of Richard III (Richard III Society, 1983) p.18, citing grants made at Nottingham, Doncaster and points north from 27 April onwards.

7 Compare the report of the battle of Bosworth in Leicestershire (22 August 1485) being recorded by the York City Council the following day, 23 August.

8 C.C. pp. 170-1.

9 It is not inconceivable that while Richard eventually prepared to move his royal entourage to York, Anne herself might have headed separately and more speedily towards Middleham.

11. Sword of State of the Prince of Wales

Sword of State of a Prince of Wales as Earl of Chester, British Museum

c. 1473–83 Prov: Hans Sloane Collection

Gothic Art for England 1400–1547 (Marks & Williamson, V&A, 2003)

Steel, copper alloy (latten?), champlevé enamel and lead

1.83m (5ft 8in)

Of exceptionally large size, this sword has a broad, double-edged blade (German, made in Passau or Sollingen) of flat hexagonal section with, on each face of the forte, a double fuller changing to a single one and, on one face, two small running wolf marks inlaid in copper alloy.

The cruciform hilt is entirely of copper alloy, originally gilt, decorated throughout with pounced scrollwork, and engraved foliage and inscriptions in Gothic letters (much rubbed); the few words that have been deciphered appear to be invocations to the Virgin in Latin and Low German. It comprises a single arched cross of diamond section tapering to beak-like tips; lead-filled octagonal pommel, with a circular recess within a slightly raised moulding on each face, one filled with a copper disc enamelled with the cross of St George, the other now empty; grip, tapering towards each end and formed of two riveted scales of plano-convex section sandwiching the tang, each inlaid with two copper panels enamelled with shields of arms, three a side, arranged to be viewed when the sword is point upwards.

They are, from top to bottom:

Side 1:

Prince of Wales (under a crown and supported by kneeling angels, all engraved);

the ancient kingdom of North Wales (according to English heralds);

the Duchy of Cornwall.

Side 2:

The Earldom of March;

the Earldom of Chester;

unidentified (silver a chief azure).

The combination of identified arms indicates that the sword could only have belonged to one or other of two Princes of Wales, both named Edward: the eldest son of Edward IV who was his successor as Edward V, given the title with that of Earl of Chester in 1473; and the son of Richard III, who received them in 1483. Since their only entitlement to a sword of state was as rulers of the Palatine of Chester, this sword must have a connection with it: it is most likely to have been the one that would have been carried before the elder Edward in 1475 when, according to Ormerod, he ‘came to Chester in great pompe’.

***

Pamela Tudor-Craig, Richard III Exhibition Catalogue, The National Portrait Gallery (2nd edn 1477)

Of all the appurtenances … the only one which appears to have survived is the state sword made, or rather hurriedly adapted, for the new Earl of Chester. It has always been called the sword of Edward, son of Edward IV as Earl of Chester. However, there is no recorded ceremony of investiture of Edward IV’s son, and if it had been made for him there is no reason to suppose it would not have been made in the normal manner. This, on the contrary, is an older German sword to which the arms of the Prince of Wales have been added.’ [Plate 54]

***

British Museum Information Label

A two-handed sword used by the Prince of Wales. Its huge size makes it a potent symbol of royal power. The steel blade was commissioned from Germany and bears a mark of two ‘running wolves’. Along the edge of the handle are invocations to the Virgin Mary, which may have been intended as a protective charm. On both sides of the grip are panels engraved with heraldry; the identified arms signify that the sword belonged to one of two Princes of Wales.

Illustration created by Geoffrey Wheeler

10. Lord Protector and High Constable briefly summarized

When I first published my book Richard III: The Maligned King in 2008 I was already examining the role of the High Constable of England in relation to the trial of plotters described on p. 131. This became p. 154 in the revised 2013 edition. By 2013 I had also researched Richard’s powers in his combined roles of High Constable and Lord Protector. I re-examined the execution of Lord Hastings, and on p. 98 of the 2013 edition (see above) stated my opinion that Richard had given Hastings a summary trial at the Tower under the Law of Arms.

When I first published my book Richard III: The Maligned King in 2008 I was already examining the role of the High Constable of England in relation to the trial of plotters described on p. 131. This became p. 154 in the revised 2013 edition. By 2013 I had also researched Richard’s powers in his combined roles of High Constable and Lord Protector. I re-examined the execution of Lord Hastings, and on p. 98 of the 2013 edition (see above) stated my opinion that Richard had given Hastings a summary trial at the Tower under the Law of Arms.

In 2015 I then published Richard Duke of Gloucester as Lord Protector and High Constable of England in which I set out the laws of treason in Richard’s day, and explained the Constable’s power to hold an ad hoc court and pass summary sentence without appeal. Later, in 2018, Dr Anne Sutton published her paper The Admiralty and Constableship of England in the Later Fifteenth Century, where she concurred with my opinion of the summary trial of Hastings (p. 205) : ‘there were present lords and knights such as Sir Robert Harrington, Sir Charles Pilkington and Sir Thomas Howard, able to form a tribunal’.

I realize that my little book on Richard as Protector and Constable is rather a lot to take in at once, so I recently produced the following summaries for a friend and he found them helpful. They’re very very condensed, of course, and the two ffices are entirely different. By the 15th century the office of High Constable of England had already existed for centuries but there was very little in the way of a paper trail … and then in the 16th century it became purely ceremonial. By contrast, the office of Lord Protector was invented in 1422 and was defined in precise detail by Parliament … and then developed almost unrecognizably in later centuries. They converged with Richard Duke of Gloucester in 1483, as they had with his father the Duke of York in the 1450s. My talk ‘Six Months in 1483’ explores what happened when they did.

HIGH CONSTABLE OF ENGLAND. A Great Officer of State appointed by the king. Had a variety of duties, of which my concern is with his judicial role relating to offences against the crown. Presided over the Court of Chivalry which was a court of civil law with its own officers and legal paraphernalia. Had its own precedents, of which details little known because seldom recorded. In trying treason the Constable was empowered to act on simple inspection of the facts, without customary form of trial and without appeal. Where the term ‘crown’ appears here it means the ‘position’ or ‘office’ occupied by the king with its long-established prerogatives and responsibilities. A distinction was made and was well understood between the king’s office and the person(s) occupying that office and/or exercising its authorities and functions for the time being. Hence you could have a Regent or a Protector or a Council (etc.) taking over a variety of the king’s prerogatives and responsibilities, including authority over prerogative courts like that of the Constable, Steward, etc.

LORD PROTECTOR OF THE REALM. An office unique to England, invented during Henry VI’s infancy, with responsibility for homeland security: ‘the name of protector and defender, which implies a personal duty of attention to the actual defence of the realm, both against enemies overseas, if necessary, and against rebels within, if there are any, which God forbid’ [Rot. Parl. iv, 326b, item 26]. Humphrey Duke of Gloucester was so appointed by the King’s Council in 1422 and ratified by Parliament (with the Council reserving to itself all other royal functions) in order not to have a regency. Richard Duke of York was so appointed in 1454 and 1455. During these appointments certain precedents were set regarding the Protector’s powers and modus operandi. Having a personal responsibility for the actual defence of the realm against rebels meant that the Protector was personally empowered to take on the crown’s authority in dealing with rebellion (which God forbid), i.e. treason.

RICHARD DUKE OF GLOUCESTER was appointed Lord Protector in May 1483. He had already been appointed High Constable for life in 1469 and had held the position for over 13 years. Thus he combined the power to identify and suppress rebellion (as Protector) with the power to take summary legal action against treason in his own court (as Constable) under the Law of Arms.

Richard III: The Maligned King (2013) p. 98 and enlarged extract

9. Princess Joana and her Three Kings

© Annette Carson 2020

Readers of Richard III: The Maligned King will remember the striking portrait of Joana, the Holy Princess, sister of King John II of Portugal, which was featured in my colour section. It was partnered with an image of John’s successor, King Manuel I of Portugal. The reason being that a marriage treaty under negotiation in 1485 provided for Joana to be Richard III’s second queen had he lived to wed again, and Manuel (the young Duke of Beja as he then was) to be Elizabeth of York’s royal husband.

These illustrations had huge relevance for me, because mine was the first book about Richard III (to the best of my knowledge) that illustrated and examined in depth the myriad implications of the proposed Portuguese marriage treaty. My interest was not merely that we were here looking at Richard’s potential future wife and England’s future queen: even more important were several other aspects.

1. Joana, born in the same year as Richard, was a significant political figure as evidenced by her being given the role of regent in her father’s absence. From the death of her elder brother (by 1455) she was heiress presumptive and was given the title Princess of Portugal rather than the usual title Infanta. Later, thanks to her extreme piety, she became known as the Holy Princess. It cannot be emphasized too strongly that in the summer of 1485, before Henry Tudor deposed Richard III and set about blackening his name, the Portuguese royal family had no qualms about arranging his marriage to their revered princess, a fact ignored by mainstream historians including Charles Ross. Clearly she and her family were not taken in by rumours about multiple murders – and especially not by gossip being circulated in England to the effect that the king was a wife-killer.

2. This is particularly notable in view of the Holy Princess’s religious devotion, expressed in her desire from an early age to become a nun. While Joana begged to be allowed to take the veil, her family unsuccessfully attempted to arrange a succession of dynastic marriages for her, putting forward two royal dukes and three kings (see below). Nothing came of these proposals and Joana eventually was allowed to retire to the monastery of Aveiro where she died unmarried; she was later beatified (though not canonized), and the three crowns she was offered feature prominently in her iconography. The last of these crowns was that of England.

3. In 1963 Domingos Mauricio Gomes dos Santos published his work on O Mosteiro de Jesus de Aveiro; this included the 15th-century account of how Joana, pressed for a response to the offer of Richard’s hand in marriage, retired for a night of prayer and meditation. During this a dream or vision of a beautiful young man appeared to her, saying that Richard ‘had gone from among the living’. Next morning she gave the firm answer that if Richard still lived, she would go to England and marry him. But this was August 1485, and the next news she received was that of Bosworth.

4. For me, an important aspect of this whole episode was the fact that the Portuguese treaty was clearly not the only possible marriage open to Richard. To ensure the succession, many options would have been under consideration by his council in the light of Queen Anne’s evidently terminal illness, and rumours even suggested that a marriage with his niece Elizabeth was one of them. Much has been made of Sir George Buc’s report of a letter written in February by Elizabeth of York to the Duke of Norfolk, asking him to promote a possible marriage for her, which commentators influenced by the aforementioned gossip have traditionally taken as an encouragement of Richard’s incestuous desires. I could not reconcile this assumption with the facts, and anyway the letter’s wording was ambiguous; there seemed to be too many political and practical reasons militating against it. I have addressed them at length in The Maligned King so I will not examine them here. What struck me forcibly was that the obvious purpose of Elizabeth’s letter was to enlist Norfolk’s advocacy on some matter of mutual concern – clearly unnecessary if both she and her uncle already wanted to marry each other!

On investigation, in which I enlisted the help of my knowledgeable contact António S. Marques, a valued source of information on Portuguese history, I established that there were actually two possible Iberian marriages on the cards simultaneously, the other being with the Infanta of Spain. Alarm at this alternative was expressed in meetings of the Portuguese royal council and reported by Álvaro Lopes de Chaves, writing in the 1480s. Thus I formed my conclusion, published in 2008, which I still maintain and which has since gained support: that Elizabeth desired Norfolk to speak to Richard advocating the Portuguese marriage in preference to the Spanish one – for the simple reason that only Portugal offered a royal match for her with the young Duke of Beja: not only a member of the royal family but also close to her own age, two qualities which were unlikely ever to present themselves in any other suitor.

This is why it was important for me to find images of Joana and Manuel for my book, emphasizing and illustrating for the first time this future as envisaged by Richard III, which traditional historians had consistently overlooked. As with all my illustrations I took pains to find images that were as authentic as possible and closely depicted the reality of the period. In this I was once again assisted by António. The portrait of Joanna he was confident about; but of the number of paintings depicting Manuel there was none that António considered, hand on heart, reliable enough to recommend. Hence we decided upon the truly authentic statue that ornaments the portal of the Mosteiro dos Jerónimos in Lisbon, which contains Manuel’s tomb.

I promised to return to the offers from three kings for the hand of Princess Joana, and this allows me to add a little to her story. Recently I was contacted by António Marques with the news that a programme about the Holy Princess and the monastery of Aveiro had been broadcast on Portuguese television, and this is the link: http://www.rtp.pt/play/p1623/e179707/visita-guiada. It’s a feast for the eyes even if one is unable to follow the dialogue. From 23:00 onward it discusses the various marriage projects and the depiction of three crowns at Joana’s feet, of which I have done my best to extract a detail below.

The three crowns were said to represent the Dauphin (or perhaps the King) of France; the King of the Romans and future Emperor Maximilian; and King Richard III of England. However, António agrees with D.M. Gomes dos Santos that the suggestion of the Dauphin or King of France seems to be untenable in both cases. The almost contemporary source Álvaro Lopes de Chaves names among Joana’s suitors the Duke of Brittany (Francis II), the Duke of Burgundy

(Charles the Bold) and the King of Sicily. According to António Marques, who applies exacting standards of research, this last is almost certainly the third of the three crowned heads. The circumstances of the King of Sicily’s marriage offer were recorded by Álvaro Lopes, who noted that the negotiations came to a halt when this suitor died ‘almost simultaneously’ with the death of Joana’s own father. This points to Charles IV, titular King of Sicily (and of Naples), 5th Duke of Anjou, who succeeded King René of Anjou in 1480 and died in December 1481, four months after Joana’s father Afonso V. The waters had been muddied by Álvaro Lopes who described him as grandson to King René, whereas he was actually René’s nephew.

António’s research has also recently taken him to the complete O Mosteiro de Jesus de Aveiro, now available online at http://memoria-africa.ua.pt/Library/ShowImage.aspx?q=/diamang/diamang-v65-II-2&p=60. Having reviewed for the first time the full transcription of the ‘Memorial’ of the Holy Princess attributed to Sister Margarida Pinheiro, he has discarded the idea that this was a second- or third-hand account, written by a nun who supposedly had not necessarily known the Princess Joana. He now has little doubt that the author was indeed Sister Margarida who was there at the time and knew the Princess well: ‘she was at her bedside when she passed away, and is reporting on events she followed closely, some of which she probably witnessed first-hand’. Certain dates and events in the account are known and independently corroborated in other sources, and ‘the whole story narrated by Pinheiro, with or without the premonitory dream embellishment, is probably much nearer the actual events than I used to think.’

8. William Hastings and the Post-Election Resignations of 2016

In my book Richard III: The Maligned King I considered what the reason might have been for Hastings’s attack on Richard on 13 June 1483, as reported by Dominic Mancini (I use the normal modern Anglicization of Mancini’s name, as I do for all proper names).

Many ideas have been put forward, but they seem to coalesce around two principal motives. To understand them, one must remember the intrigues that went on in high places, and the jockeying for position in Court circles which represented the key to power, wealth and privilege. It is not difficult to find parallels today.

1. Hastings viewed with alarm that the King’s Council had drafted a policy prolonging Richard’s protectorship even after the expected coronation of Edward V [see Chancellor Russell’s draft speech to Parliament]. Previously King Edward IV’s confidant and right-hand man, the 52-year-old Hastings was now witnessing the extreme favour shown by 30-year-old Richard to his equally young compeer the Duke of Buckingham, and realized that he was about to become yesterday’s man. He had expected to continue wielding his accustomed influence with Edward IV’s son, the new boy-king Edward V; but now Hastings saw his career about to be eclipsed under Richard who had his own group of confidants.

2. The news of Edward IV’s first secret marriage (precontract) to Lady Eleanor Talbot had come to light, which meant he had committed bigamy when he secretly married Edward V’s mother Elizabeth Woodville. The circumstances of this bigamous marriage had the shocking effect of bastardizing its offspring, which meant that the government was wrestling with the problem of whether the illegitimate Edward V should succeed or be replaced, Richard being the next eligible heir. Hastings had spent years building close ties with the Prince of Wales, but (as in 1. above) a Court in service to Richard III promised little space for Hastings and dealt a mortal blow to his expectations.

These are perfectly good motives, but if you place yourself in Hastings’s shoes, it is questionable whether they were sufficient for him to lay his life on the line so publicly, irrevocably and, as it turned out, literally.

This is why I favour a third alternative, which is based partly on Hastings’s known dealings with Elizabeth Woodville before Edward married her, and partly on Mancini’s characterization of Hastings the womanizer.

Even allowing for the exaggerations of rumour and juicy tittle-tattle, Mancini’s repeated references to Hastings make his relationship with Edward IV very clear, having been the latter’s “loyal companion from an early age”. “Hastings was not only the author of the sovereign’s public policy, as being one who had shared every peril with the king, but was also the accomplice and partner of his privy pleasures.” Edward was himself described by Mancini as “licentious in the extreme”, “most insolent to numerous women after he had seduced them”, “pursuing with no discrimination the married and unmarried, the noble and the lowly”, and when he tired of them, “gave up the ladies much against their will to the other courtiers”. Edward had other “promoters and companions of his vices”, one of them being the Marquess of Dorset, with whom Hastings was feuding at the time “because of the mistresses whom they had abducted or attempted to entice from one another.”

If even half of this is true, it paints a picture of a Hastings known to be a long-standing intimate of Edward’s adventures in seduction. Given this public reputation – and given what Donald Trump calls ‘locker-room talk’ – he could scarcely fail to be identified as complicit (if not actively a procurer) in Edward’s succession of sexual partners.

To quote from The Maligned King: “With the investigation of the precontract Hastings could well expect to face some unpleasant questioning as to his knowledge of Edward IV’s liaisons with the young women who entered into secret marriages with him. If suspicion emerged that he connived at the Woodville marriage in full knowledge of the Talbot marriage, he could expect to pay the time-honoured penalty of disgrace and punishment as the royal adviser whose influence led to the downfall of his master’s heirs. Richard had already made it clear what he thought of those who encouraged his brother’s grosser predilections.”

And so I come to the parallel with Theresa May’s team leaders, Nick Timothy and Fiona Hill, who fell on their swords after the 2016 election. In those dire circumstances it seems scapegoats had to be found for their party’s loss of an overall majority in Parliament, and these two very close personal advisers of Mrs May were singled out for ritual humiliation and public disgrace.

Fortunately for them the phrase ‘falling on their swords’ was metaphorical. In Hastings’s case it was less so. As a man seasoned in military action he decided on a last desperate throw of the dice to eliminate the one person whose removal could swing the pendulum of power back towards earlier incumbents, opening the door to Edward V’s accession, and securing Hastings’s previous expectations of high office. Compared to expulsion and disgrace, for one who had so much to lose, he probably considered it worth the gamble.

7. Why it HAD to be the Tower of London

© Annette Carson 2021

To celebrate the new year of 2016 I threw caution to the winds and set my imagination free to recount a purely invented scenario. It concerns one of the most baffling incidents of the Richard III story: the plot that resulted in the execution of William, Lord Hastings.

First let me run through the factual circumstances of the incident itself. We’ve had far too much smoke and mirrors already. Forget Tudor stories of witchcraft and withered arms; forget the small-talk of strawberries suddenly transmogrified into murderous fury; forget convenient self-incrimination provided by go-betweens. Colourful as these devices are, any creative writer will recognize them as classic misdirection. They’re calculated to distract from the pretence at the heart of the Tudor fabrication: that a Protector of the Realm, a mere five weeks into his appointment, could get away with unprovoked daylight murder of a peer in the middle of London, in front of witnesses, and still retain the complete confidence of the King’s Council and the Three Estates of Parliament who then collectively elected him King of England.

By contrast, there is a credible, gold standard, on-the-spot report, written in 1483 (newly available in my own 2021 translation), which we ignore it at our peril. It was provided by the Italian cleric Domenico Mancini who was in London at the time, as an agent for the French court, and reporting within a few months of the event. Although not present himself, he would have gleaned information immediately, notably from the proclamation made public in London. So, stripped of editorial opinion,* and translated from his original words, Mancini’s report provides the following information:

1. Hastings was executed for a treasonable attempt on Richard’s life, having brought hidden weapons into a meeting so that he could launch a surprise attack on his victim.

2. Two other influential ringleaders were arrested with him for the same offence, but being in holy orders they escaped with their lives thanks to Benefit of Clergy. One was Archbishop Rotherham, a man raised to the chancellery by Edward IV; the other was Bishop Morton, ‘a man of many designs and much boldness’, with a career in party intrigue dating back at least twenty years to the Lancastrian era of Henry VI (mark those words).

3. These men were reported to have been assembling together previously in each others’ houses.

4. The incident took place at about 10.00 a.m. at a meeting in the Tower of London, several other witnesses being present.

5. Men at arms, stationed nearby, were summoned by Richard upon his cry of ‘ambush’.

6. A public proclamation to the above effect was issued right away.

7. Richard at the time had made no claim on the throne.

8. The coronation of the young King Edward V was still in schedule for 22 June.

*I need to add that in Mancini’s opinion Hastings was charged ‘in the false name of treason’, but it should be noted that this visiting Italian was not qualified to pass judgement on the treason laws of England, nor was he present to see what actually happened. Under the Law of Arms it was Richard’s special prerogative, as High Constable of England, to try the crime of treason in his own Constable’s Court, to pronounce on guilt and to pass sentence without the possibility of appeal. The evidence for this appears in my recent book on the offices of Protector and Constable.

We have a couple of other facts provided by the Crowland Chronicle, written following Richard’s death some two years later. The author expostulates over the beheading and arrests, on which he spends many words of personal opinion and judgement. But it’s significant that he provides very little factual detail, especially compared to Mancini. From what he writes, it is clear that he was no more present in the Tower than the Italian was. Let us again strip away editorial opinion and look at the chronicle’s two relevant facts:

1. The meeting was a Council meeting called for 13 June.

2. Council attendance had been divided in advance (by the Protector) so that one group met at Westminster and another at the Tower. I shall examine this insinuation that it was Richard who laid the trap, which should be compared with Mancini’s comment that his cry of ‘ambush’ was prearranged.

To complete the preliminary scene-setting, it hardly needs re-stating that from early May 1483 the Protector and Council represented the legally constituted government of England during the king’s minority. We have no eyewitness account that contradicts the facts officially announced by proclamation and recorded by Mancini, i.e. that Hastings was the aggressor in a treasonable assassination attempt. Nevertheless it is glaringly obvious that this treasonous attack was early on parlayed into entrapment of blameless individuals by the wicked Lord Protector. Even when the aggression by the conspirators is admitted, it is sometimes claimed that the plot to assassinate Richard could not have been treason because they were acting ‘to protect Edward V’. Any such claim is rooted in misapprehension of the circumstances (Mancini testifies that Richard had made no move to prevent the coronation), and ignorance of the constitutional position, since Richard held the dual offices of Protector of the Realm and High Constable of England, in which it was his role, not that of Baron Hastings, to protect the realm from treason.

Working with these background facts, I have my own ideas of what the conspirators had in mind. And it had everything to do with why they chose to attack Richard at the Tower of London. My imagined scenario starts with the question of motive. They may have had varied personal goals, but I see it as an attempted coup d’état by a disaffected group who agreed in that they saw themselves slighted, and their lucrative status sidelined, by the incoming Protector’s charmed circle. All had hitherto enjoyed influential roles within the court and the Prince of Wales’s council, and their collective strategy was a familiar one: to encircle the underage king and exert power through him. All it required was to eliminate the Protector.

A. Hastings had found himself yesterday’s man, losing his valuable royal influence while the young Duke of Buckingham, busily collecting offices and rewards, now had the ear of Richard in the same way that Hastings had once enjoyed the ear of Edward IV.

B. Archbishop Rotherham, a protégé of the Woodville queen’s family, had lost his office of Chancellor to Bishop John Russell, an extremely able candidate by all accounts. Like many others, Rotherham could no longer look for patronage to the Woodvilles, now absconded, disgraced and excluded from government after their failed attempt to oust Richard.

C. The demonstrated long game of Bishop John Morton, that supreme political operator, certainly centred on grasping any opportunity for subversion in the interests of his Lancastrian patron, Lady Margaret Beaufort, and her son Henry Tudor. Ambition is a far more credible motive than supposedly tender feelings for Edward IV’s heir, and it’s worth reflecting that Morton’s preferred patrons would go on to reward him handsomely by creating him both Archbishop of Canterbury and a cardinal.

Having learnt that Hastings, Rotherham and Morton were meeting together, Richard was concerned enough to write to his northern supporters, a few days before the Hastings attack, requesting armed support. It would not have been a wise tactic to suggest threats emanating from inner-circle councillors and clerics, especially if he didn’t know precisely who was involved, so he named his opponents as the usual suspects: the Woodvilles. In later years suspects would have been picked off one by one with the knock on the door in the small hours of the morning, but this was not Richard’s way: we know of no arrests in the days leading up to 13 June. In order to submit them to the full force of justice, I conclude that Richard needed the conspirators to commit an overt act of aggression. So he and his aides would have been on full alert waiting for someone to show their hand. The key would then be to play along, ready to counteract any move when it came.

This is why Richard is unlikely to have been the one to split the Council overtly into two groups. He wouldn’t want anything out of the ordinary to tip off his opponents that he was forewarned – although he might have supported the suggestion of such a split meeting made by someone else, knowing that their plan of attack required an attendance that was smaller than usual. By my calculation it was the Hastings group who needed to have Richard attend a meeting of a small group peopled as far as possible by their own supporters. Mancini’s account suggests a small group in a small room, rather than a large council-chamber. We don’t know anything about the agendas or purposes of particular Council meetings, and we can safely ignore misinformation by Tudor writers. But we do know preparations were well in hand at this time for Edward V’s forthcoming coronation. Although the Crown Jewels were kept at Westminster Abbey, much of the State Regalia was held at the Tower of London; so an examination of long-disused regalia, preparatory to formal approval by the king, might well have provided the excuse for a high-ranking select committee meeting at the Tower. Meanwhile Chancellor Russell’s group could be making arrangements with Abbot Esteney to take an inventory of the priceless jewels at Westminster.

This is just a random idea – there could have been any number of excuses for a division of the Council. Richard would agree innocently and plan accordingly. As a tactician he would have sized up the likelihood that this was to be the chosen moment. He was a great believer in the pre-emptive strike. All he needed to do was wait until all were assembled, meanwhile having loyal men stationed nearby, armed and listening, ready to respond to his call. Then he would enter the room and present himself as a target.

I’ve covered motive, means and opportunity, but the most difficult thing about history is to figure out what was intended compared to what actually panned out. For example: if we didn’t know it was true, we would surely disbelieve that Julius Caesar’s opponents assassinated him personally and publicly on the steps of the senate. What were they thinking?! In terms of politics (and it’s politics that particularly interest me) a decision depends not only on what to do, but what to do afterwards. What you can get away with, who is for you, who against, and who will support the winning side. Hastings and his co-conspirators would have made their judgements accordingly, and this brings me to the question of why two clerics had to be involved.

We know there were six or seven arrests – quite possibly more – and quite possibly others were never caught. But why would Hastings, the old war-horse, involve men of the cloth like Morton and Rotherham in an assassination attempt, and how were they recruited? This last question is answered in the person of Morton, whose skills as a life-long political operator were reported even by the foreigner Mancini (remember Morton’s later recruitment of Buckingham to the Tudor cause!). He was just the man to bring in an already disgruntled Rotherham. And why? The aim was to bolster the group’s credibility in the plan of action to be followed once Richard was despatched.

To be secret, sudden and swift was the key. Hastings would have stationed a number of retainers to back up his attack, unaware of course that Richard had quietly set his own men on the alert. The take-over must be instant, replacing the Protector’s leading position in the government. This meant gaining immediate control of the king. Which explains why the fatal encounter HAD to take place at the Tower. If they’d done it anywhere else (despite the misdirection of Tudor writers) they’d have had no access to the king, and how would they have managed the aftermath? So the scheme was to take swift action at the Tower, while the rest of the Council was elsewhere, leaving no one any chance to object. A group headed by the Archbishop of York and Bishop of Ely, moving swiftly and commandingly, had the authority to sweep all before them unchallenged as they proceeded to the royal apartments … and likewise the presence of leading prelates would reassure Edward V right away that he need fear no plot against his own life. If any guards did ask questions, a plausible excuse was that they were hurrying to ensure the king’s person was still safe – something the Tower guards would accept and probably assist in.

The plan rested on a vacuum being left after Richard was removed, with little option but to accept the new regime – one that strongly resembled the state of play before the protectorate had been established. It might have worked; but, as with the Woodvilles’ earlier attempted coup, Richard was clever enough to prevent it. And because he escaped with his life while punishing the perpetrators, his enemies were able to twist the events to portray him as the guilty party.

This text revised 2021.

6. ‘After 500 years of controversy we may finally have solved the mystery of the Princes in the Tower!’

These remarkable words ended the final narration of the Oxford Films production ‘The Princes in the Tower’, aired on 21 March on the eve of Leicester’s events commemorating and reburying King Richard III.

This trumpeted ‘solution’ of the mystery relied on the closing revelation by that celebrated media personality Dr David Starkey, who claimed as a final flourish that he had found new evidence which provided proof of Thomas More’s story that James Tyrell confessed to killing the sons of Edward IV. This, it will be remembered, was a story unique to More until it later became the authorized version.

The Guildhall, London, from ‘Woodcut map’ c.1560

Despite sources including Fabyan postulating other varieties of demise and other perpetrators, Tyrell emerged as the favourite culprit purely because lazy historical writers adopted Thomas More’s writings, later used by Shakespeare, as literal fact (Dr Rosemary Horrox [ODNB] is more circumspect: ‘More’s elaborately circumstantial account which is, however, demonstrably inaccurate in detail’). Many of More’s fans put forward the argument that he was too saintly to have made it up. On the other hand, students of English literature (and those who have studied More’s other writings) are entirely familiar with his penchant for making things up, often in a manner too colourful to repeat in polite society. That More’s ‘Richard III’ is a work of creative literature is in fact a long-established and widely accepted tenet among experts in the genre.

It is worth mentioning, indeed, that Thomas More himself warned his readers that the Tyrell story was only one of the versions he had heard, and More made no claim to have ‘found’, ‘discovered’, and still less to have ‘verified’ that it was correct: merely that he had ‘heard by such men and by such means as me thinketh it were hard but it should be true’. Scarcely a ringing endorsement. Those who believe that More ‘knew’ the truth of the matter have yet to supply any convincing historical proof.

Returning to Dr Starkey’s revelation on TV, this seems to hinge on his claim to the effect that Henry VII and Queen Elizabeth were present at the Tower of London during the trial of Sir James Tyrell. I have attempted without success to discover whether Starkey has written of this great discovery in any learned journal.

Starkey’s statement continues (in a transcription supplied to me): ‘They’d just lost their son, they’d just lost Prince Arthur, and yet both of them go to the Tower on the days of his [Tyrrel’s] trial, and are there the day before he’s led off to execution. This simply has not been picked up. It’s in the Treasurer of the Chamber’s accounts and you can actually trace the movements of the king and queen. They’re there, he’s there, and something’s going on!’

Narrator: ‘For David Starkey, the presence of the king and queen at the trial vindicates Thomas More’s claim.’

Starkey: ‘It tells me that More is 99% right. There is some sort of “confession”. What we have there is as near as we can get to the truth.’

Narrator: ‘If Tyrell killed the princes, then it was his master Richard who was the real author of the crime. After 500 years of controversy we may finally have solved the mystery of the Princes in the Tower!’

Now, then, where shall I start?

** Yes, there was a fully reported trial of Sir James Tyrell and several alleged co-conspirators (‘a high-profile show trial’ is how Thomas Penn describes it in Winter King).

** This trial had no connection whosoever with the sons of Edward IV. The defendants were accused of aiding and abetting Edmund de la Pole, Earl of Suffolk, whose aim was to overthrow Henry VII.

** Tyrell was detained for two months in the Tower. However the trial itself, and Tyrell’s conviction for treason, took place not at the Tower of London but at the Guildhall, on 2 May 1502. He was executed on 6 May. [See above extract from Ralph Agas plan of London, around 1560, showing Guildhall in the centre.]

** Why should Dr Starkey claim that the presence of the king and queen at theTower had any relevance to the mysterious disappearance of the sons of Edward IV nearly 20 years earlier? Easy: because history writers of Starkey’s ilk overlook that the Tower of London was London’s foremost royal residence. ‘Everybody’s gotta be somewhere,’ as Spike Milligan’s character Eccles memorably remarked.

** More’s identification of Tyrell as killer of the princes ‘rests on a confession that Tyrell was said to have made between his condemnation and execution. No copy of the confession survives’ [ODNB again]. Not only does no ‘copy’ survive, there is not even any passing reference to any confession by any contemporary witness or writer. Nor is any statement on the scaffold recorded. To be accurate, therefore, the ODNB article ought to have stated ‘a confession that Tyrell was said BY THOMAS MORE to have made’, since it was More who uniquely generated the otherwise totally unsupported story that Tyrell confessed. Polydore Vergil, for example, makes no mention of any confession.

Why would Dr Starkey have us believe that the presence of the king and queen in the Tower of London in 1502 offers the remotest proof that More is ‘99% right’ in his story that Tyrell ‘confessed’?

If we are invited to suppose or deduce or speculate that a confession was wrung from Tyrell, why should it relate to anything other than the matter in hand: the Earl of Suffolk’s conspiracy?

This is not historical research, it is TV grandstanding, and ought to be roundly condemned as such. Back when I worked at Thames Television we had teams of researchers whose job was to check and verify what went into our programmes. Presumably proper research has now been junked in favour of Wikipedia and prating celebrities, who are believed because what they say, however ill-informed, makes for good viewing.

The representative of Oxford Films who asked me to appear in the programme, aghast that I refused, protested that their company had a good reputation for factual documentaries. ‘We will not be favouring one argument over another’, he told me in an email message, adding that they would be ‘allowing a range of opinions to be heard without any editorial judgement being made about which side (or sides) of the debate are right.’ Well, Ted White, perhaps you should have sent a copy of your email message to the scriptwriter who wrote, on the basis of Dr Starkey’s ridiculous statement, ‘we may finally have solved the mystery’.

The viewing public was ill served by allowing Starkey to air his delusions of grandeur; and I am also tempted to add that the individuals who were cast as visual portrayals of leading characters, like Richard III and Anthony Earl Rivers, clearly displayed where the ‘editorial judgement’ of Oxford Films lay.

5. Knowledge and Remembrance are Enough

To many people the knowledge that Richard III’s body has been found is enough. It’s enough to know that some of the casually cruel lies about him have been exposed for the falsehoods they are: the evil hunchback with the withered arm, twisted in mind and body; the supposed desecration of his grave and vindictive destruction of his remains; even the inference that nobody ever cared enough to search for his last resting place.

To many Ricardians it is enough, also, that from the exposure of such calumnies comes a degree of reassessment, small but growing. Perhaps not for the hidebound, but certainly for those who have open hearts and minds. We can all attest to evidence of this in our daily interactions, and in feedback at talks and book signings.

His official tomb, love it or hate it, may end up in the city where he was buried with scant respect in 1485. But his spirit, and the way we relate to it, does not wholly reside in his mortal remains. Leicester was never a Mecca for Ricardians, except to admire James Butler’s handsome statue, donated in the halcyon days of Jeremy Potter’s Richard III Society. No better tomb effigy could have been devised: and still it is there to be freely admired and photographed.

Even so, many of us may never be able to visit the city, or may not wish to. What is to be learned there that we do not know already? Certainly Leicester is investing in new tourist attractions (and the university is manufacturing lapel badges), but I hear of no great investment being made in disinterested Ricardian research.

Until recently I had never visited the tomb of George VI, but that is not a reflection of the immense affection and respect I have for our brave wartime king. I was happy to find that King George rests in a place of great beauty and sanctity, steeped in our island’s history and royal traditions. But the location and surroundings, and the nature of his memorial, are immaterial to the essence of our last king’s courage and quiet achievements. If he had been killed in action and buried at sea, his memory would still be cherished.

So it is with Richard III: knowledge and remembrance are enough. I have fond memories of the Society’s ledger stone in the little Victorian cathedral in Leicester. When I learned that the interior was to be … shall we say, ‘redesigned’ … I already had a suspicion in 2011, long before we found Richard’s grave, that I probably wouldn’t relish the visual experience its modernizers had in store. The latest redesign, making space for Richard’s extraordinary tomb, seems to confirm my apprehensions. But we are all free to go or stay away: there are many ways to celebrate and commemorate. Our sensibilities are personal to us, and we can’t expect – or insist – that the rest of the world should share them.

Yet as long as there has been a chance for Ricardians to maximize the honour and respect due upon the king’s reburial, there has always been a case for attempting to negotiate with the Leicester authorities while there is still time. Even though, having been a professional negotiator in my day, I would scarcely apply the word ‘negotiate’ to the tactic where one side announces a final decision seven days before a scheduled meeting. But I admit I am oldfashioned about these things.